January 30, 2026

Dr. Kyoko Nakano, Director of Sustainability Department, Eisai Co., Ltd., visited Kenya in October 2025 with Dr. Katsura Hata, who has long been involved in Eisai’s efforts for Global Health, to participate in a strategic meeting for mycetoma drug development and to observe current clinical setting for the mycetoma patients. Although she had seen glimpses of Africa through Japanese media before her visit, the actual experience drastically changed her impressions and perspective. This report comes from Kyoko Nakano, who remarked, “This trip reaffirmed the importance of visiting the sites in person.”

Kyoko Nakano, Project Leader, Mycetoma Drug Development, Director of Sustainability

(Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, PhD)

Kenya is in a country in Eastern Africa with a population of more than 56 million and an area of approximately 1.5 times that of Japan. The equator runs through the middle of the country, which shares borders with Somalia to the east, Ethiopia and South Sudan to the north, Uganda to the west, and Tanzania to the south. The Great Rift Valley runs through western Kenya from north to south, shaping the region’s diverse landscapes and climates. We visited the area around Lake Turkana, located at the northern tip of the valley. At 5,199 meters, Mt. Kenya is the country’s highest peak and the second-highest mountain in Africa. Kenya is home to over 40 ethnic groups, with English and Swahili serving as its official languages.

On the first day, we visited KEMRI (The Kenya Medical Research Institute:) in Nairobi with colleagues from our partner DNDi (Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative: a non-profit body engaged in drug R&D projects for treatments including neglected diseases). Established in 1979, KEMRI is a national research institute that has become a world-renowned hub for malaria and other medical research. It was established with the support of JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) who continues to support the institute through technical assistance and opportunities for Kenyan researchers to be dispatched to Japan. The site also houses the Kenya Station of Nagasaki University’s Institute of Tropical Medicine (NUITM), where numerous researchers engage in their daily studies.

The facility is well-equipped, and through conversations with its researchers, I deeply felt their mission, dedication, and passion to foster the health of Kenyan people and contribute to the nation. There are several potential collaborative research sites in Kenya for our upcoming mycetoma projects, including KEMRI.

On our second day, we flew from Nairobi early in the morning to visit the County Referral Hospital in Lodwar, the capital of Turkana County. We were accompanied by Dr. Borna, DNDi’s Mycetoma Strategy Lead, and a principal investigator for DNDi’s ongoing epidemiological study in Kenya, as well as hospital staff.

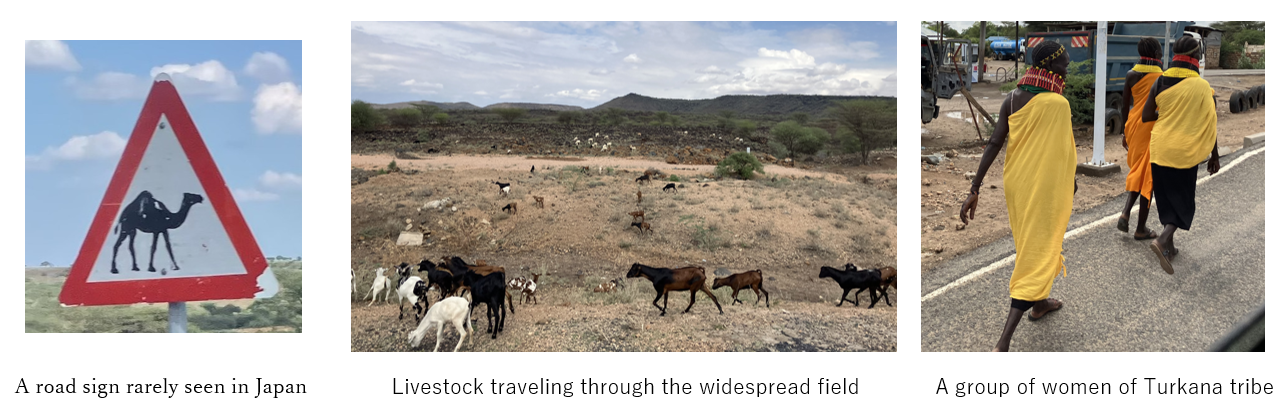

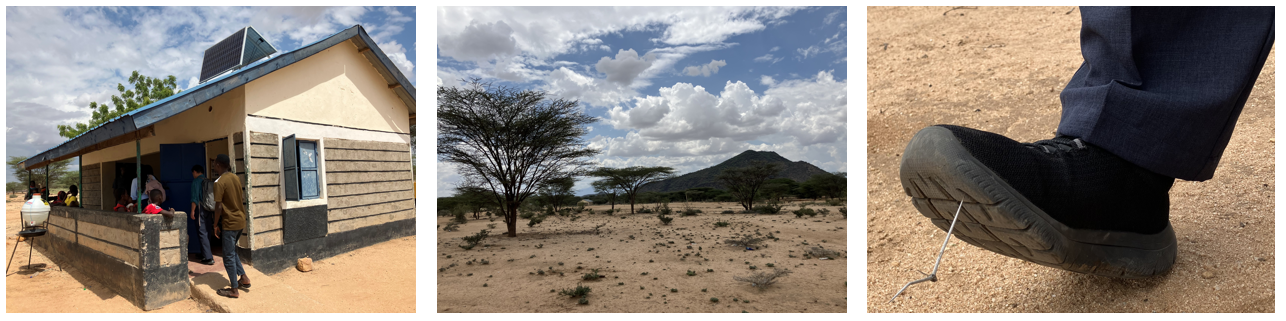

Upon our arrival in Turkana County, on the way heading toward Lodwar County Referral Hospital, I noticed a gradual decrease in vegetation, and increase in land with brown soil. It is a hot and dry region where most residents engage in pastoralism, living a nomadic lifestyle with their livestock. Although we occasionally saw donkeys and camels which are viewed as a symbol of wealth, goats are the primary livestock here. Turkana County has a poverty rate of approximately 80%, the highest in Kenya, with a high level of unemployment among the population.

Lodwar County Referral Hospital is the only referral hospital in the region, serving patients from across the county and occasionally from neighboring counties. While smaller medical facilities are scattered throughout the county, they are often far from patients’ home. Furthermore, the nomadic lifestyle of the local population makes it challenging to provide continuous treatment and follow-up. Inpatient and surgical wards, as well as recovery rooms, were crowded with people, with high portion of pediatric patients.

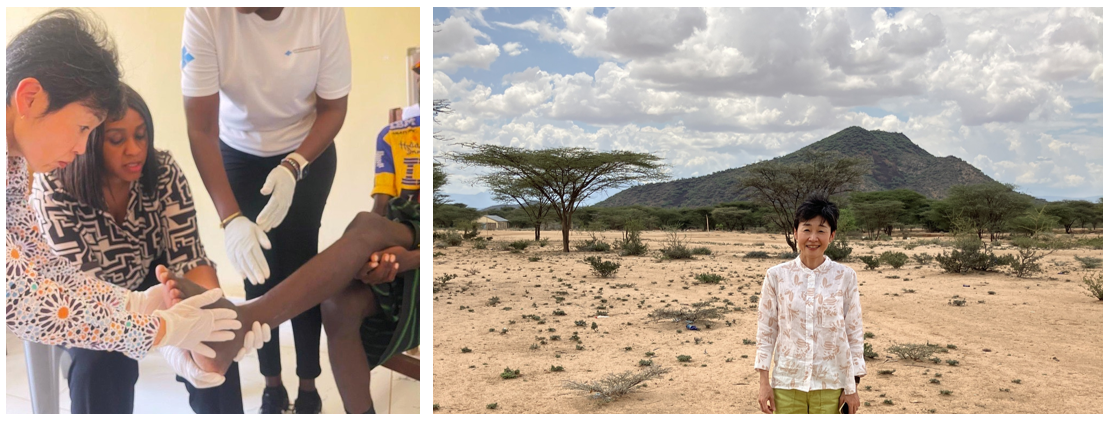

On the day of our visit, we met three mycetoma patients. Since all live far from the hospital, it takes a long time for them to travel, and those with jobs must take a day off. In the local community, there is stigma associated with various diseases, including mycetoma, which sometimes extends even from the patients’ family members. Some patients appeared to have aggravated their symptoms by traditional remedies that may not be considered entirely appropriate by Western medical standards, such as applying mud from Lake Turkana to the affected areas.

While the routes of infection of mycetoma remain to be fully elucidated, it is believed that the disease is caused by environmental pathogens entering the body through injuries e.g. from plant thorns such as those of Acacia. One patient developed swelling in the sole a few months after attempting to remove a painful boil (likely not mycetoma at that stage) using an Acacia thorn. It is possible that the patient unintentionally infected himself with pathogens on the thorn. This case might have been prevented had there been sufficient disease awareness.

As the lesions caused by mycetoma expand, they cause pain, making walking and other daily movements difficult. For those living a nomadic life, difficulty in walking means losing one’s livelihood. Furthermore, in a community with limited transportation, hospital visits with a painful leg pose a major challenge. It also makes it difficult for patients to participate in community events and enjoy social life. We learned of the realities, including cases of divorce due to mycetoma, and patients who attempted suicide from psychological distress. This made us realize the scale of impact this disease has on both individuals and the community. If they had easy access to treatment, their lives might have been very different. Our experience in this day made us realize that local life is completely different from our situation, where medical care is readily available.

Patients we met and their symptoms

On the third day, we visited Lomil Dispensary. It is a small, isolated facility situated in an arid area. It was only reached after driving more than 10 kilometers on an unpaved road from the main road. Livestock and their feces were scattered around the facility, and Acacia thorns sharp enough to pierce through rubber shoe soles were found everywhere on the ground. People would need to be cautious even just walking around bare foot or even in sandals.

On that day, Lomil Dispensary saw seven patients, including one suspected case of mycetoma. As with the previous day, we realized the difficult circumstances these patients are in. There are two types of mycetoma - bacterial and fungal. While bacterial mycetoma is curable with appropriate care, we have encountered cases where the condition worsened due to limited hospital access from leg pain, premature discontinuation of treatment, and the use of antibiotics without prescription or a definitive diagnosis of whether the infection was bacterial or fungal. Self-medication without a diagnosis or prescription must be avoided to prevent the development of antimicrobial resistance. This once again highlights the importance of disease awareness.

Upon returning from Kenya

Mycetoma patients are in a highly difficult situation in terms of healthcare access. With limited transportation, a nomadic lifestyle involving long-distance walking, and cultural background of close human relationship and communal living, patients bear various daily life challenges and psychological distresses. Witnessing the challenging circumstances faced by each patient and their uncertainty about the future, I realized the impact of mycetoma is much greater than I imagined. Through this visit, I came to realize that understanding cultural and social backgrounds where patients belong, rather than just their disease features, is essential for understanding mycetoma and implementing countermeasures. At the same time, I became aware of the need for disease awareness targeting both patients and community members to ensure appropriate knowledge and treatment. Seeing the strong desire of patients to overcome the disease and live their fullest life, I felt a renewed commitment to accomplish everything within our power, even on a step-by-step basis.

During our stay in Kenya, I was impressed by the warm welcome I received whenever I mentioned I was from Japan. People expressed appreciation for Japan’s support over the years and showed great trust in the reliability of Japanese products. While many challenges remain to be addressed for the patients, it is essential for all stakeholders to work in close collaboration and engage in continuous discussion. I sincerely appreciate all stakeholders including members of DNDi for their support for this trip. Based on Eisai’s human health care (hhc) concept, we will continue to engage in this field to build a foundation for better healthcare service and our future.

Please refer to the links below for past articles regarding mycetoma

Scientists Discuss the Development of a New Treatment for the Elimination of Mycetoma

Mycetoma Added to the World Health Organization's List of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)

Please refer to the following link for further details on mycetoma